Interesting Cultivated Edibles I have abandoned bigger plans (of just about everything), but I can still think and act small. Thus, as days and years pass, I plan to add to this page, perhaps 75 unique entries. There are no guiding principles, central elements, or goals. If I take a photo of an interesting cultivated edible, or already have one, and the urge comes on, I will post it. Plants are fun, and I don't want to make them work. Unless noted otherwise, all the images were taken at our Tallahassee homestead or the Farm; some photos are of plants that have been removed for one or another reason. It is illegal--I do not have phytosanitary certification--for me to provide propagation materials; in the case of citrus, with canker and greening endemic in Florida, it would also be irresponsible. Thanks for understanding. Some native edibles are featured on this page and a few honey plants are found here. Last edit: 2015-02-14

|

|

|

Hamilton No. 1 Mulberry. In 2001—within the year after Mama died—I visited her brother Herbert, who mentioned a good mulberry at Jack Hamilton’s nearby homestead. He and I went there, and I collected propagation wood. Only one of that collection survived, and it grows in my front yard (image left 2006-05-27) at Tallahassee. Other trees have since been propagated from it, including one planted near our home for us and three planted for wildlife in 2011 at the farm. Mr. Hamilton transplanted two seedlings from Melvin Vickers’ in Ambrose, GA. The seedlings turned out to be different—the one I propagated blooms a little earlier than the other. Both seedlings were a minimum of 100-150 feet from the closest mother tree. The distance and the difference between the two indicate that they were seedlings, not root sprouts. (Not wishing to be a pessimist, I still think it is practical to consider trees on the lower limit of chill requirements.) Uses: fresh eating, excellent; crisps, excellent; morat, good enough; wine, fair. Other images of Hamilton No. 1: left image (unreduced file);

|

|

Watson No. 1 Pecan. Pecans were usually an integral part of old homesteads in South Georgia; indeed, most had small orchards. Elsewhere, I have briefly discussed the orchard on the Jerry S. “Buck” Sutton Old Home Place, which trees were similar in some respects to those in the orchard per se on the joining Samuel W. Watson Home Place. According to my mother, both greatgrandfathers planted those orchards and mulberry orchards from trees obtained from a traveling salesman (whether the same salesman or time, I do not know). However, several "house trees" on the Watson place yield better nuts and possibly were planted at a different time. Larry Watson, who owns this place now, remembers that his father, Samuel L. Watson, said that all the trees were seedlings.

Other relevant images: left image (unreduced file); metrics; shuck-opening; nut x-sec; grandfather Mark A. Watson (Thanks to A. Kenneth Womble for making the main image. Thanks also to the property owner, Larry S. Watson (my first cousin) for giving me unrestricted access and sharing nuts.) **************** 2012 Cultivar Map at Farm. rev 2015-02-14 Location of Jackson, Lakota, Elliot. 2014 Cultivar Map at Farm. rev 2015-02-14 Location of Eclipse, Ellis, Jackson. 2015 Cultivar Map at Farm. rev 2015-02-14 Location of Amling, Excel, and Gafford. Pollination Plan. rev 2015-02-14 In case replacements are needed. |

|

Celebrate Citrus Propagation I (Ichang Lemon). With different degrees of success depending on cold protection and cultivar, various citruses and citrus relatives can be grown in South Georgia and North Florida. Both scion and rootstock contibute to hardiness. Fortunately, citrus is very easy to bud (left, 2005-07-27); when the bark is slipping (June), a bud with a sliver of wood (in this example, Ichang lemon) is inserted under the rootstock bark by use of an inverted T. The bud is wrapped tightly, given time for the cambia to fuse (ca. 6 weeks), and then unwrapped. If the bud is healthy--perhaps 75% of the time--the rootstock is cut off, relieving the latency of the bud imposed by auxin from the apex. Rootstock is critical. Poncirus trifoliata (trifoliate orange, inedible) is my clear choice. It is resistant to Phytophthera and canker, confers hardiness, limits the size of scion, and contributes to sweetness. I bud about 6-8" from the ground to help protect the scion from Phytophthera, but at least one expert (the late J. Steward Nagle) recommends grafting much higher, feeling the hardiness in the scion is improved. I prefer using Flying Dragon, a mutant of Poncirus, which confers reliably dwarfness and is easily distinguished by the curved thorns and contorted shoot. Both the species and the mutant overgrow the scion. It is not usual that one finds this rootstock available as it takes about a year longer to produce a marketable plant, but it is worth searching for if one doesn't propagate his own. Uses: Though seedy, Ichang lemon can be used as an ordinary lemon; ade is virtually indistinguishable from typical lemonade. For a homestead that utilizes much sour citrus, Ichange lemon is a good choice. Other relevant image(s): Immature Ichang lemon ;

|

|

Celebrate Citrus Propagation II (Changsha Mandarin). In most plants, seeds are produced sexually implying generally that seedling traits are unpredictable. However, there are notable exceptions, including many citrus. In these cases, the embryo forms adventitiously from sporophytic tissue, viz. the nucellus. In this way, the seed produces a plant that is genetically identical to the single parent. Thus, when such a cultivar as Changsha mandarin (left, 2005-11) has properties consistent with its use as a scion and rootstock, it can be propagaged by seeds. Changsha is one of the more cold-hardy citrus, an added bonus, but if the shoot of a seedling freezes, it can regenerate from the root. In general, seedlings take longer to bear than budded (or rooted) plants as they must pass through juvenility (only about one year in the case of key lime, but up to 15 years in some grapefruits). In some plants, embryos are produced both sexually and asexually. Flying Dragon, in the preceding entry, is an example. About 90% of the seedlings are true-to-type (as indicated by curved thorns) and the remainder--which are rogued from the propagation bed--have straight thorns, indicating the wild-type, i.e., zygotic seedlings. Changsha is a consistent producer, but in my experience with neglectful culture, fruit quality varies (tending toward dryness and being insipid). It is always very seedy (20-40 seeds per fruit). Some crops, however, equal satsuma, which is my highest praise. Overall, it is a valuable dooryard fruit.

|

|

Celebrate Citrus Propagation III (Thomasville Citrangequat). Thomasville citrangequat (left, 2001-02) provides a third example of plant propagation. The limited definition of species applied to the macroscopic world is "a population that produces fertile offspring sexually." Plants, however, are much more interesting and often sexually reproduce across species or even genus lines. Thus a citrangequat is a cross of a citrange (Citrus sp x Poncirus trifoliata) with a kumquat (="golden fruit"), which is Fortunella. Thus, this plant is produced sexually from three different genera, hoping to produce a delicious fruit (from Citrus) on a very cold-hardy plant (Poncirus can survive north of Washington DC) with delayed emergence from dormancy (from Fortunella). Thomasville itself was selected in Thomasville, GA, from Swingle's breeding program around the turn of the 20th century. Uses of Thomasville citrangequat: in late fall, before freezing, as a lemon/lime substitute. One year, Nedra made a batch of key-lime pies, some from authentic key limes and others from this citrangequat. I served samples to my naive students--keeping track of which student was served which type of pie--and asked the students to complete a form for recipe suggestions. There were suggestions (e.g., more butter in the graham crust), but not one questioned the fruit, though Floridians consider themselves first-rate experts on key-lime pie!!! I could of course distinguish the key lime pie by its more tart character, but this little experiment shows that this bullet-proof weedy citrus certainly has uses. In a mild winter, when the fruit does not freeze, it will mature and become more-or-less edible out of hand. It can be propagated by seeds. Other relevant image(s): Fruit on tree in September; |

|

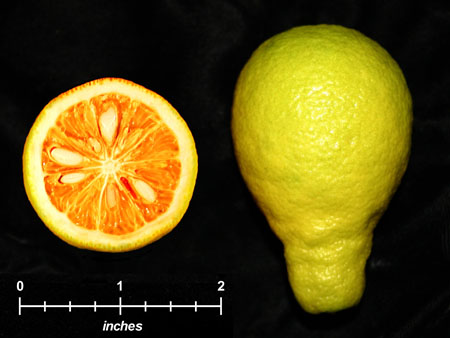

10/3&4 Citrangequat. After a professor identifies a potentially useful genotype, it is evaluated by committee to determine whether it should be released as a cultivar. To qualify, the genotype must be judged a significant improvement in some way from existing cultivars. (Of course, commercial breeders are not included in this generality.) I "found" one citrangequat at the Citrus Arboretum that apparently failed to make the grade. It was not part of their inventory and was sitting over in a pot. On searching their records, "Vicky" found it had been obtained from the USDA (Leesburg or Orlando?) in 1981, and it had been labeled as "Citrangequat Hybrid," but whether that meant the citrangequat itself is a hybrid or the plant itself is a hybrid of citrangequat and something else is unknown. Two number series, 10/3&4, were associated with the plant, perhaps Row Number and Plant Numbers, but the numbers could refer to anything, e.g., Grove Number . . . . Regardless, that is all known of the history of this little gem. With permission, I obtained budwood and have maintained it on Flying Dragon for more than a decade; I dissent from other opinion apparently and think it is a valuable unique resource. It produces an 85-gram fruit and yields more juice than a Thomasville citrangequat. The juice is pleasant and is unburdened by detectable bitter skunkiness of many Poncirus hybrids. Other relevant image(s): blooms (Thanks to A. Kenneth Womble for making the main image.) |

|

Cattley Guava. Cattley guava requires little attention, except for protection from cold. Fortunately--because of its invasiveness in South Florida--it will not survive our winters. As an out-of-hand dessert, its sublime musky flavor is peerless. We have grown both the red ("strawberry") and yellow ("lemon") and favor the latter because it is somewhat larger. If one has the means and desire to protect this ornamental plant, it should be part of a homestead plan in my opinion. No longer able to devote 2 h a day to maintaining potted plants, I have let it slip out of our collection. Other relevant image(s): Ripe Fruit

|

|

Feijoa (aka Pineapple Guava). The late Ralph Sharpe is exactly the kind of person we should encourage our daughters and sons to emulate. He left mankind many cultivars that extend the range of many species into hitherto impermissible environments; he answered the call of his country (Captain, WWII); and, to me, essentially a stranger, he left the cream of his decades-long selections of feijoa. As a sideline, he initially planted 3700 seedlings, selected from those, and again, planted out 3700 seedlings. My plants are seedlings selected from the latter planting. He gave some of them to me as plants grown in the greenhouse of his retirement center; others, from seeds he and I collected before his project was going to be bulldozed. How lucky am I? Feijoa produces a beautiful hedge and provides foliage for decoration. The petals (main image) are edible, being fun to graze on or include in salads. The minty soft texture is unique. Where feijoa shines, though, is in the production of fruit. The interior resembles a kiwi, but the taste, with hints of tropical fruit, is extraordinary. Many cultivars have been selected, but are usually not available through ordinary channels. As most plants on this page, feijoa requires little care--I've never sprayed mine and have not watered them since they became established. Other relevant image(s): fruit on ground (shown because some experts report that it will not fruit here) ;

|

|

Avocado (aka Alligator Pear). Overall, 1998 was a good year for us. Though it was not to last, Mama had recovered some from her stroke two years earlier; Will finished his first year in medical school; and, Elizabeth's anthropology degree was in sight. Nedra and I enjoyed planning for our upcoming research trip to Germany and side-trip to visit a former postdoc, Gianni Bedini, in Pisa, Italy. That year, we also enjoyed "local" travel to Monticello (figs and other plants along the submural walls!), to Roanoke, to the SC mountains (roadside apple stands were still common then!), and to Homestead, FL. Although most of the trips were associated with business, we added enough time for our own pursuits, notably tours of tropical-fruit farms personally guided by avocado expert Dr. Thomas L. Davenport (thanks, Tom). Importantly, in the context of this page, we purchased an avocado tree. Both Nedra and I love avocados, and I particularly enjoyed culturing this Mexicola tree (the Mexican race of avocado is more cold-hardy than the other two races (Guatemalan and West Indian), and Mexicola produces an oily avocado, the only type I consider edible; contrast: Choquette). In our climate, Mexicola fruit reach egg size in June and mature in late July/early August, achieving commercial quality. Unfortunately, we lost our avocado; whether correctly or not, I attribute the loss to Armillaria mellea, fruiting bodies of which I tentatively identified nearby. Growing avocados provides tremendous satisfaction, but an equal amount of work (viz., cold protection). With laurel-wilt fungus spreading to our area, we have decided to postpone replacement. |

|

Potato A deadly nightshade, the potato was domesticated in the Andes, though edible Solanum species were cultivated in Pre-Columbian times as far north as the southern U.S. border. They exist in wondrous variety--3000 types--and we have grown and enjoyed only a small portion of this diversity (ready for storage, left). Depending on how one counts (wet weight, dry weight, calories), potatoes are one of the top five food crops in the world. A war has been named after them (Kartoffelkrieg), a childish and divisive political sobriquet coined (Freedom Fries), and a country depopulated when Phytophthera (''plant destroyer") caused a crop failure. Each of these topics and more deserve book-length essays, but here they are only noted to emphasize the central role of this one plant in our global food supply (e.g., potato vendor in New Dehli) and civilization. The edible portion is a tuber, a swelling of an underground shoot. In our area--because tuber formation is inhibited by warm soil --the challenge is to plant a quick-maturity cultivar as early as possible. Mama's planting date was Valentine's Day, which I think is 2-3 weeks too late (but I acknowledge having lost "seed" in cold wet soil). In brief, potatoes are propagated vegetatively from portions of northern-grown seed potatoes (where virus-infected plants can be rogued). Seed potatoes are cut into egg-sized pieces that contain an "eye" (again, the tuber is a shoot, so lateral appendages--the eye is a bud--arise on the surface). After a few days, the cut surfaces heal (suberization), and seed pieces are planted 4-8" (as implied, tuber formation will be above the seed piece). Two special rewards come from growing potatoes. Cooking and eating them, of course, is a no-brainer. The other reward is the suspense of digging them--because our storage is limited, we selectively dig and eat most of them as they mature. Seeing that crack in the soil reminds me of Forrest Gump, who famously said, "Life is like a box of chocolates . . . ." |

Last edit 2012-08-08. |

|

Return to Documentation for this page. |

|